Many Afghan “Kochyan” (nomads) inhabit tents made of bands woven from the wool of goats and sheep by women from these communities, who move every season between lowlands to high mountain pastures (or “Elbandans”) in search of fresh fodder for their flocks. To this day, it is common to see clusters of black tents across the Afghan countryside, or on the outskirts of towns, as nomad families follow a process of migration that has taken place for generations.

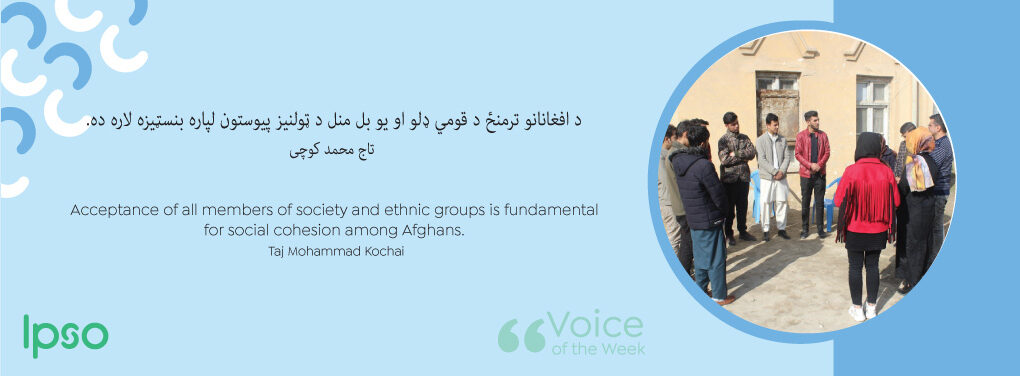

A 45-year-old member of a nomadic family, Taj Mohammad Kochi, who this spring moved with his family from Nangarhar to Balkh, says: “We go from Balkh to Nangarhar in winter to take care of our animals and return to Balkh in spring to ensure that they have sufficient pasture year-round. We transport our tents, household items, children and the elderly on camels, as they are able to carry heaving loads over significant distance and can do without water for a prolonged period.”

Nomadic groups have historically played an important role in trade across Afghanistan, and earned a fearsome reputation among those who threatened their seasonal migration along long-established routes. Afghan nomads today belong to a variety of ethnic groups – Pashtun, Baloch, Uzbek, Turkmen, Kyrgyz, Hazara, Ferozkohi, Jamshidian, and Aimaq – each with distinct traditions, costumes and dialects. All however share a similar primary source of livelihood: raising camels, sheep, and goats. A nomadic family may raise some 300 to 400 animals, selling milk, yogurt, cow dung, wool, and goat fat to meet their domestic needs.

According to Taj, their nomadic way of life means that they rarely benefit from public services such as education, access or health care, and in some cases their presence is not welcomed by settled communities, with whom they often compete for access to pasture for their flocks. In recent years, this has resulted in conflict between villagers and nomadic groups, as pressure on pastures grows. Another member of the group, Kochi Khatool explains: “Land that we relied on for pasture for our flocks is often now used for agriculture, which means that we can’t sustain ourselves. Many families have little option but to give up the nomadic life and settle in one place”.

Another reason for nomads to change their way of life is the difficulty of accessing public services, such as health care, given that they are on the move. Taj explains: “Keeping livestock as a way of life requires us to travel, but this has consequences for our families, especially as our children are deprived of formal education.”

When a Kuchi family does settle, they may face significant prejudice from settled groups, who often shun them. As a result, they often limit their interaction to their relatives, as Khatool Kochi, who recently settled in Balkh province, explains: “We have usually lived in mountains all our lives, with a way of life that responds to this environment. It is often hard for others to relate to this, so they keep their distance”. It takes time for a nomad to adjust to a settled life and to fully integrate, and the process can be made more difficult by the attitude of others, who in many cases shun them and avoid mixing.

Khatool explains: “Our way of life is perceived to be different, so those who do not share our nomadic heritage often avoid mixing with us, so we can feel isolated. This has consequences for the wider community in which we live, as it fosters a sense of division. I wish that others could be more understanding and accepting of our traditions.”