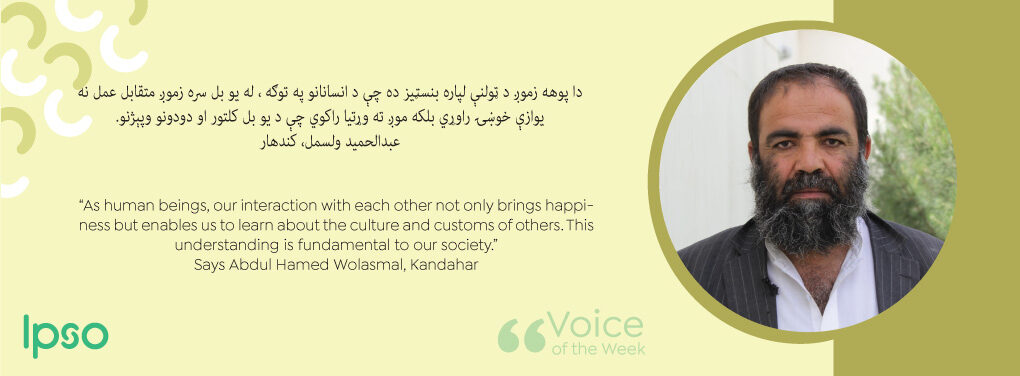

Naan-o-namak shodan (literally in Persian, to share bread & salt) is an expression used by Afghans to describe having a meal. It is commonly used when strangers get to know each other by spending time together and sharing food.

The value of befriending each other is evident in the experience of Karim, who around 20 years ago moved from Paktia, a Pashtun-majority town in eastern Afghanistan, to Mazar-e-Sharif, a city where people from all over Afghanistan live. He settled in the neighborhood of Qowaye Kar, a community of around 250 households with a diverse range of ethnic origins and backgrounds. Perhaps the most diverse and integrated quarter in Mazar-e-Sharif, the way in which the residents of Qowaye Kar coexist in harmony and help each other is unusual in an urban context.

After Karim’s mother passed away a few years ago, he had no relatives in Mazar-e-Sharif to attend her funeral. “Those who attended the ceremony were my neighbors who are mostly from other ethnic groups,” says Karim. “For me, this is what community is about – people who are with you in times of grief and joy no matter what your ethnic background is.”

Most Afghan cities have well-defined neighborhoods whose residents are predominantly from a single ethnic group or come from a specific province. There is nothing new about this – during past conflict it was a way to ensure collective security. Karim explains: “Most people coming to settle in Mazar-e-sharif gravitate to places where others from their area of origin already live. For example, there is an area where only people from central Hazarajat live, and another with only Badakhshanis.” adding “In my view, this limits opportunities to get to know and engage with one another.”

Qowaye Kar is, however, an exception to this pattern. Here, people from different areas live side by side; one of Karim’s neighbors is Mohammad Ali, a Shia Hazara from Daikundi, who explains “My neighbor on the left is a Pashtun from Paktia and on the right is a Tajik from Shamali. When I first moved here, we Shias didn’t have our own mosque, so I prayed in a nearby Sunni mosque – that would not be possible elsewhere.”

The diversity of the residents in Qowaye Kar has taken shape over the past two decades, and provides them with opportunities to get to know each other and develop a true sense of community built on what they share rather than their differences.

Karim believes that “the power of naan-o-namak shodan brought us closer together. We attend funerals, weddings and other events together, visit and support each other in sickness and loan each other money. We sit together to discuss and deal with our shared problems within the community” adding that “we realize that this friendship and support can extend beyond our own ethnic group or religious sect.”

Mohammad Ali says that living at close-quarters with people from other ethnic groups has helped change attitudes. “I used to have many preconceptions about other ethnic groups when I lived in Daikundi, and this made me fear them. By getting to know others, this has fostered friendship and trust.”

“Much of this mistrust and fear comes from lack of familiarity with each other” Karim explains. “Hopefully our experience in Qowaye Kar can serve as an example elsewhere, so that more Afghans engage with one another and see how they can in fact coexist – and be stronger together.”